Listen to the audio version of this story. For more, subscribe to our podcast.

When John Grado listens to music, he sits in a comfortable chair with the lights turned down. Sometimes he closes his eyes. He listens for the distinctive xylophone tones in Duke Ellington’s “Malletoba Spank,” and for the sound of individual applause as Eric Clapton strums his guitar at the beginning of a live performance of “Signe.” And when Ella Fitzgerald sings “A Night in Tunisia,” John wants to feel like she’s in the room, serenading him: The moon is the same moon above you…

A customer who puts on a pair of headphones made by Grado Labs, the company John’s uncle founded in 1953, will hear Duke Ellington, Eric Clapton and Ella Fitzgerald the way John hears these musicians. He’s been using these same 15- to 20-second snippets of music for the last two decades to calibrate Grado headphones. The process is carried out in a well-appointed listening room on the top floor of Grado Labs in Brooklyn’s Sunset Park neighborhood. The room’s dark blue walls are decorated with paintings by John’s father; one of them depicts company founder Joseph Grado performing the part of Othello in the Verdi opera. Joseph Grado, who died in February, was a watchmaker, inventor and tenor, and the audio equipment company he started at his kitchen table in 1953 channeled those passions into a viable business that remains under family ownership.

“Every product we make is a reflection of us,” John says. “We put out what we like, and we’re fortunate that people like what we make.”

Grado Labs makes just two kinds of audio equipment, phonograph cartridges and headphones, and the Grados—John and his older son, Jonathan—aren’t concerned with maintaining a rigorous schedule of new releases. Product development reflects the Grados’ personal experiences with their creations more than market research or aesthetic trends. When the Grados feel they’ve come up with enough meaningful improvements over a current version, they release a new product. The company has introduced just three generations of headphones in 25 years, and it hasn’t advertised since the 1960s. This way of doing business works well for Grado, which has built a devoted following among audiophiles and music industry professionals.

“They like that feeling of being a little bit exclusive, of being a little bit of a club and a family that you get to be a part of when you purchase their product,” says Lauren Dragan, headphone editor at The Wirecutter, a website that provides in-depth gadget reviews. “It’s something that they’re very smart about in terms of how they handle their marketing….When you open [a Grado box], there’s a welcome letter: ‘Congratulations and thanks from us, the Grados.’ For the type of person who looks for that kind of headphone experience, that really connects.”

For most of its history, Grado was known for its phono cartridges, the devices at the end of a turntable’s tone arm that convert the needle’s vibrations into electrical signals. Joseph Grado studied watchmaking at a vocational high school in New York and worked for Tiffany & Co. before developing an interest in audio technology, eventually patenting the stereo moving coil cartridge in 1959. (In his design, tiny wire coils vibrate within a magnetic field as the needle moves through a record’s grooves.) Joseph Grado started making phono cartridges at his kitchen table. In 1955, he moved the operations of his fledging company into his Italian immigrant father’s fruit store in Sunset Park. The fruit store is long gone, but Grado Labs is still there.

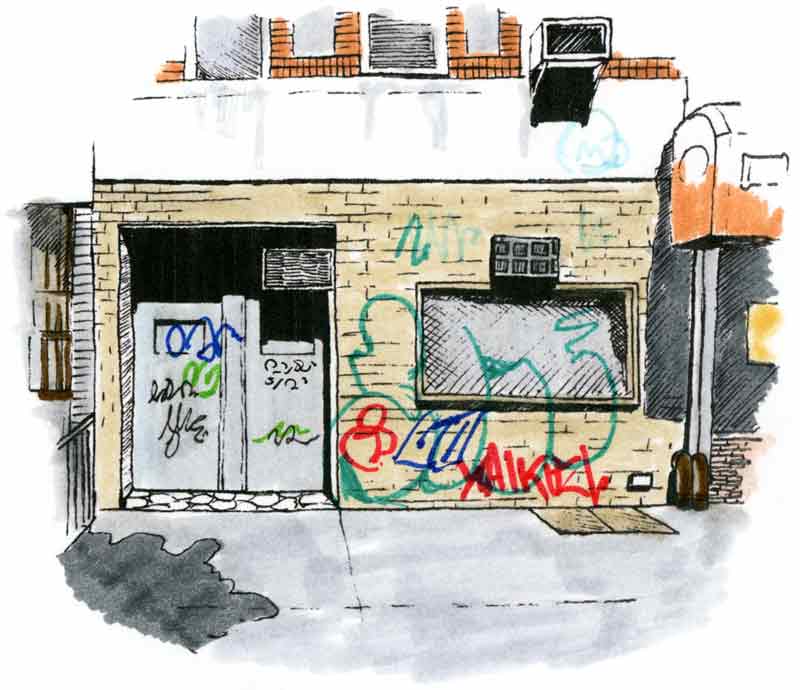

With its forbidding metal doors, graffiti-covered facade, and lack of identifying signage, the Grado building gives no indication that it’s where some of the audio world’s most revered headphones are made. It doesn’t look like a family home from the outside either, yet that’s where Jonathan Grado spent the first eight years of his life. The Grados lived on the top floor, and company employees worked on the lower levels. The inside of the building still bears signs of the Grados’ years there. The masking tape notches of Jonathan’s childhood height chart remain on a wall in one room; in his old bedroom, a Baby Goofy wall decal peeks out between towering stacks of boxes, and his glow-in-the-dark stars dot the ceiling.

The building is such an important part of Grado’s history that John thinks of it as “a lucky rabbit’s foot.” It’s remained a constant in a neighborhood that has changed significantly during his lifetime. When he was growing up around the corner, Sunset Park was mostly Irish and Scandinavian. By the 1980s, those residents had moved out in large numbers, and many businesses closed their doors. The neighborhood stopped holding its annual Norwegian Day Parade. Then a new wave of primarily Chinese immigrants began arriving in Sunset Park, setting up businesses along Eighth Avenue. Now, as ever-rising rents push Brooklynites farther into the borough, the neighborhood appears to be on the cusp of gentrification, bringing to Grado’s doorstep the kind of consumer who’s likely to be a fan of the company’s products.

“They’re a legendary audiophile headphone,” Dragan says. “They have that wonderful hands-on, family, Americana-New York side that I think a lot of people really love and appreciate.”

Tuning In

John’s first official day of work at Grado was July 3, 1965, when he was 12 years old. His task: cutting little plastic pieces that protected phono cartridges during shipping, for a penny per piece. He cut 700 the first day, caught on quickly and cut 7,000 the next day. The job was the first of many John would tackle at the family business before joining full-time after college. He became owner in 1990, a crucial period for the company as it entered the headphone market. By then, he’d already taken over day-to-day operations for several years.

Grado started developing headphones in the late 1980s, when it looked like the phono cartridge was becoming obsolete, thanks to the growing dominance of the compact disc. Both cartridges and headphones are electromagnetic devices, so Joseph Grado believed the company’s expertise in the legacy product would translate to a related area. At the time, however, no one at Grado saw the iPod or the iPhone coming. The company thought the future of headphones would be students using them with laptops.

Grado sold about 150,000 pairs of headphones last year and expects to top that number in 2015. The company makes in-ear headphones but is known for its open-back, on-ear headphones. The open-back style is a less popular choice for commuting and walking around because wearers can hear outside noise, and people nearby can hear what’s coming out of the speakers. Even so, the sudden ubiquity of digital music players and headphones was a boon to Grado: Consumers proved willing to pay hundreds of dollars for products like Beats by Dr. Dre. Grado’s mahogany ear cups and leather head straps offer a markedly different aesthetic than the glossy metal of Beats—and the Grado men would argue with conviction that their products sound much better—but both brands have benefited from the popularity of high-end headphones. While Grado headphones start under $100, the upmarket models sell for well over $1,000.

“Ten years ago, a lot of people associated headphones with what was given out for free on an airplane and all of a sudden, with the onset of Beats, we saw headphones commanding multiple hundred-dollar price points,” says Sean Murphy, senior manager of industry analysis at the Consumer Electronics Association. “The quality of a lot of these new headphones is debatable and that’s kind of beside the point. The reality is they’re commanding those price points and the ostensible value-add is that they are better sounding.”

We didn’t think we’d still be making cartridges at all close to 2015.

Perhaps even more surprising to the Grados than the advent of the iPod is the resurgence of vinyl, a phenomenon keeping phono cartridge production at higher levels than the family anticipated. Grado once sold 10,000 cartridges a week. In 1990, the company sold just 12,000 over the year.

“Cartridge sales have gone to 65,000 per year, and we didn’t think we’d still be making cartridges at all close to 2015, so it’s great,” says Jonathan, who oversees marketing and social media. “But we used to have the cartridges built and we’d send them out, and now it’s basically made to order. They’re coming in fast.”

According to the Consumer Electronics Association, annual sales of new turntables to dealers in the United States haven’t topped 1 million units since 1984. This year, the industry group projects sales of just 69,000 turntables. But the CEA’s Murphy says he believes there’s an active market for both used turntables (and used vinyl) that’s not reflected in the data, and that it’s the upgrading or refurbishing of older units that is giving sales of related components—like phono cartridges—a modest boost, even if vinyl is still a fraction of the overall music industry.

“Without any facetiousness, any numbers are better than zero,” says Murphy, who counts himself among those who recently dusted off an old milk crate of records and started listening to vinyl again. “When you start talking about thousands or tens of thousands versus zero, which is where the industry effectively was a decade ago, when it was all digital all the time, it has been an interesting—bordering on incredible—story that, from what I’ve seen and heard, doesn’t show any sign of slackening.”

Playing On

John and Jonathan make cartridges themselves at a small bench in Grado’s cramped basement. Because the company’s manufacturing facility is in the old Grado family home, the basement resembles the workshop of a do-it-yourselfer run amok: Amid small appliances and organized bins of tools stands an automatic injection-molding machine that barely fits into the space. The machine pumps out plastic parts for headphones. An older and smaller manual machine, which the company bought secondhand in 1953, makes cartridge parts.

“My dad likes this machine when we can fix it,” Jonathan says. “But if there’s a part that actually gets broken, then we need to find someone who still has a mold for that part and we have to get it made—which is incredibly annoying, but it’s been 62 years, so I guess we’re going to keep doing it.”

Most of the machines in the Grado basement were cobbled together from other pieces of equipment to perform specific tasks, like drilling a pair of holes in a cartridge part. On the upper floors, a staff of fewer than 20 puts together the cartridges and high-end headphones by hand. (Grado’s in-ear headphones are made in Asia.) The company gets its mahogany ear cups from a woodworking shop in New Jersey whose sole customer is Grado. Using wood in the headphones was John’s idea; he says he thought of it in the middle of the night and went downstairs the next morning to start working on a prototype. Grado’s high-end phono cartridges also use mahogany because John likes the way the material resonates.

“Everything has its own resonant frequency,” he says. “If a headphone has five different parts—and there are more than five parts—it’s all resonant frequencies, and they intertwine with each other and make noise. They distract from letting the signal come through. We can dampen them and make them work together.”

The Grados also have experience in cutting distractions from their business operations. In the early days of Grado Labs, the company made a wider range of equipment that included speakers, turntables and tone arms. In 1963, it jettisoned everything but the cartridges, its best-known product. Aside from a brief interlude in the early 1980s, when Grado released a wooden tone arm, the company has stuck to cartridges and headphones.

The two hot things in the audio world today are vinyl and headphones. Those two items have kept us as busy as we’d like to be, and I don’t think we have to do everything.

John and Jonathan have no interest in loading their headphones with more features or offering a rainbow of colors as Beats does. John, an avid reader of biographies, is fond of the quote attributed to Henry Ford: “You can paint it any color, so long as it’s black.” He’s only interested in making his products sound better and translating the purest listening experience—comfortable chair, low lighting, Ella Fitzgerald singing about the moon and the stars—to the people who buy Grado headphones.

“The two hot things in the audio world today are vinyl and headphones,” John says. “Those two items have kept us as busy as we’d like to be, and I don’t think we have to do everything.”